MCPs and Merlet

In 2017, I was a student of French composer Michel Merlet, and he introduced me to his theoretical framework called “Genèse Dodécaphonique des Modes” – a systematic approach to understanding modal structures within the twelve-tone system. This framework has profoundly influenced my approach to composition and sound design over the years.

I’ve been thinking about Merlet recently, and how musical frameworks like his create a stable foundation for tonal exploration. “Shoulders of giants” and all that. I was trying to see if I could come up with a way to codify this foundation in a tool that I can mess around with and prod a bit – I love the determinism of this system, but I wanted a way to visualize it a bit better, and maybe even bounce ideas off of it.

That’s when I learned about MCPs, which I’ll get back to in a sec..

Merlet’s System

The “Genèse Dodécaphonique des Modes” (Dodecaphonic Genesis of Modes) is Michel Merlet’s systematic approach to deriving, categorizing, and understanding various modal structures within the twelve-tone musical system. Unlike conventional classifications, Merlet’s system organizes modes based on their mathematical properties, symmetrical characteristics, and historical usage. My favorite part is how it recontextualizes tonal music away from the traditional Greek modes, it takes a step further back and begins with a simple notion – “let’s start with the octave, and keep splitting.” 1

The system was first illustrated to me in the diagram below – visually represented as a clock-like circular diagram. At 12 o’ clock, we take the octave and split it into 12 – our chromatic scale. At 1 we split once, to get C and F# – tritones, and an equally split octave. Each mode is color-coded in pairs, creating a visual map of tonal relationships. For every mode created this way, there is its “complement” mode mirrored and colored accordingly across the diagram.

Check out Merlet’s diagram below:

Shoutout to Ash Suh for making this copy for me, a while back!

Shoutout to Ash Suh for making this copy for me, a while back!

The modes are numbered from 0 to 12:

Mode 0: Chromatic (12-12=0)

The complete chromatic scale using all twelve tones. It has no complementary structure (“absence de complémentarité”) and is historically exemplified in Schoenberg’s “Valse, Cinq pièces opus 23” (1923).

Mode 0: Chromatic (12-12=0)

The complete chromatic scale using all twelve tones. It has no complementary structure (“absence de complémentarité”) and is historically exemplified in Schoenberg’s “Valse, Cinq pièces opus 23” (1923).

- Listen: Schoenberg – Fünf Klavierstücke Op. 23, No. 5 “Walzer” (Pina Napolitano, piano)

- Alternate: Full set performed by Eduard Steuermann

Mode 1: Tritone

Based on the tritone interval (6 semitones), creating an “antipodal” symmetry that divides the octave precisely in half. Historically referenced in Ballif’s “À cor et à cri” (1962).

Mode 2: 8÷2=5 (Diminished)

Created with consistent 2-semitone intervals, producing a symmetrical diminished structure. Exemplified in Messiaen’s “4e partie de l’Ascension” (1933).

Mode 3: 8÷3=8/3 (Augmented)

Based on consistent 4-semitone intervals (major thirds), creating a perfectly symmetrical augmented structure. Found in Messiaen’s “Thème et variations” (1932).

- Listen: Messiaen – Thème et variations (Daniel Kurganov, violin & Constantine Finehouse, piano)

- Alternate: Alexi Kenney, violin & Victor Asuncion, piano

Mode 4: 8÷4=7

A symmetrical mode built on 3-semitone jumps, as used in Stravinsky’s “Symphonie des psaumes” (1930).

- Listen: Stravinsky – Symphonie de Psaumes (Orchestra e Coro del Teatro La Fenice, cond. Riccardo Muti)

- Alternate: Radio Philharmonic Orchestra & Netherlands Radio Choir, cond. Peter Dijkstra

Mode 5: Pentatonic

The asymmetrical five-note scale, historically referenced in Fauré’s “Fantaisie pour piano et orchestre” (1919).

- Listen: Fauré – Fantaisie for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 111 (Alicia de Larrocha, London Philharmonic Orchestra, cond. Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos)

- Alternate: Grant Johannesen, piano & London Symphony Orchestra, cond. Sir Eugene Goossens

Mode 6: Par tons (Whole Tone)

Composed of consistent whole-tone intervals (2 semitones), creating perfect symmetry. Exemplified in Debussy’s “Voiles” from his first book of Preludes (1910).

- Listen: Debussy – Voiles (Daniel Barenboim, piano)

- Alternate: Orchestral arrangement by Royal Scottish National Orchestra, cond. Jun Märkl

Mode 7: Diatonic

The traditional seven-note scale (like major and minor scales) with its characteristic asymmetrical pattern of whole and half steps. Referenced in Ravel’s “La Laideronnette".

The diagram also shows modes 8-12, which complement modes 4-0 respectively, creating a symmetrical relationship within the system.

What makes Merlet’s system particularly valuable is how it connects mathematical properties with historical compositions, demonstrating that these structures aren’t merely theoretical but have been intuitively discovered and employed by composers throughout the 20th century.

Model Context Protocols

Large Language Models have evolved beyond simple text generation into powerful assistants that can extend their capabilities through tools - specialized programs that perform specific functions when called by the LLM. These tools enable LLMs to perform calculations, retrieve information, or generate specialized content outside their training parameters.

Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers are quickly becoming adopted as the next evolution within this ecosystem — standardized ways for LLMs to interact with external tools, data sources, and computation engines. Unlike one-off custom tools, MCPs provide a framework for developers to create consistent, reusable interfaces between models and external systems.

What excites me about MCPs is their potential to create conversational interfaces to specialized domains like music theory and sound design. Rather than building rigid user interfaces with predetermined parameters – like a plugin – MCPs allow natural language to serve as the interface to complex systems. You can ask the system to explore theoretical concepts, and it will do the computational heavy lifting behind the scenes.

For creative fields like sound design and music composition, this approach holds particular promise. Musical concepts often exist in a space between abstract theory and concrete implementation — a gap that has traditionally required significant mental translation work. MCPs can bridge this gap by allowing LLMs to reason about musical structures while connecting to the tools in the background.

In essence, MCPs create a collaborative environment where your understanding of music theory, augmented by an LLM’s broader knowledge, can directly inform technical implementation without requiring you to manually translate between these domains. You can focus on creative exploration while the system handles the technical execution.

Case Study: Shoulders of Giants

With this in mind, I decided to create a practical example — a custom tool that generates Merlet modes for any given root note. This Python-based tool would encapsulate the theoretical framework while making it immediately applicable to compositional work.

The implementation process itself was enlightening. Translating Merlet’s visual diagram into code required me to formalize aspects of the system that I had previously internalized more intuitively. I needed to define precise data structures for the modes, their symmetry types, and historical references:

from enum import Enum

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import List, Optional

class SymmetryType(Enum):

SYMMETRIC = "symmetric"

ASYMMETRIC = "asymmetric"

ANTIPODAL = "antipodal"

NONE = "absence de complémentarité"

@dataclass

class HistoricalReference:

composer: str

work: str

year: int

@dataclass

class Mode:

number: int

name: str

intervals: List[int]

symmetry_type: SymmetryType

historical_ref: Optional[HistoricalReference] = None

With these structures in place, I could then implement the core algorithm that generates each mode based on its defining interval pattern:

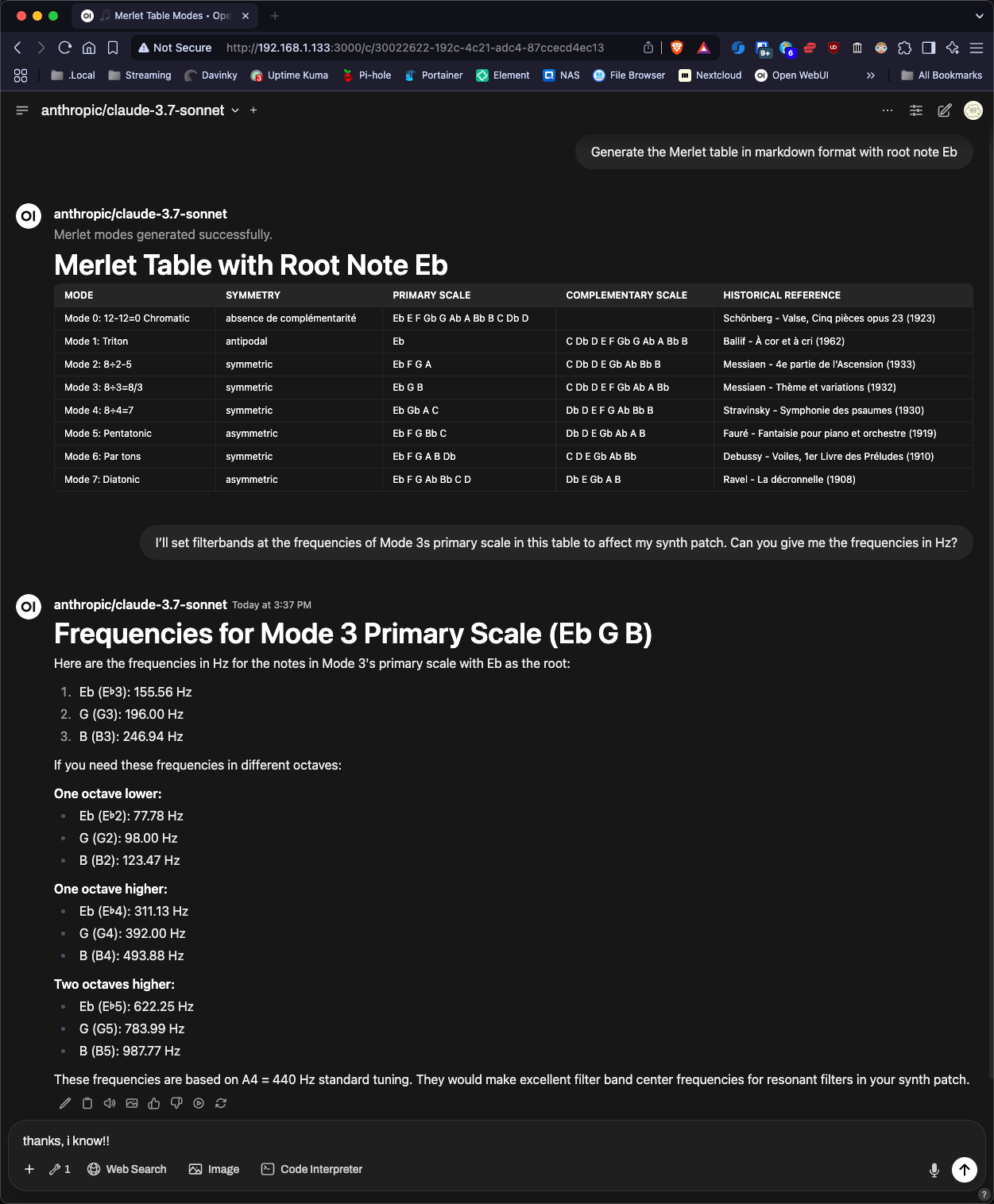

I integrated this tool with OpenWebUI, allowing me to interact with it through natural language. For example, I prompt:

“Generate the Merlet table in markdown format with root note C”

And receive a comprehensive table showing each mode, its symmetry properties, scale notes, complementary notes, and historical reference:

| Mode | Symmetry | Primary Scale | Complementary Scale | Historical Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode 0: 12-12=0 Chromatic | absence de complémentarité | C Db D Eb E F Gb G Ab A Bb B | Schönberg - Valse, Cinq pièces opus 23 (1923) | |

| Mode 1: Triton | antipodal | C Gb | Db D Eb E F G Ab A Bb B | Ballif - À cor et à cri (1962) |

| Mode 2: 8÷2-5 | symmetric | C D E Gb | Db Eb F G Ab A Bb B | Messiaen - 4e partie de l’Ascension (1933) |

| … | … | … | … | … |

Applications

The use case for sound design goes beyond just academic interest. By encoding Merlet’s theoretical framework into an accessible tool, we open up several practical applications:

1. Compositional Frameworks

Using these modal structures as starting points for compositions ensures coherence while exploring beyond conventional tonality. Each mode has its distinct emotional character and historical context, providing creative direction.

2. Sound Design Parameters

The symmetrical properties of these modes can inform synthesizer parameter settings. For example:

- Using Mode 3’s augmented structure to create equidistant filter modulations

- Applying Mode 4’s symmetrical intervals to FM synthesis ratios

- Mapping Mode 6’s whole-tone structure to granular density parameters

3. Generative Audio Systems

Algorithmic composition systems can leverage these well-defined modal structures as rule sets, particularly in adaptive game audio where tonal consistency must be maintained across procedurally generated content.

4. Timbral Exploration

The complementary structure of Merlet’s system (where each mode has its complement) provides a framework for designing contrasting but related timbres—useful for creating coherent soundscapes with internal variation.

MCP Integration for Audio Applications

While my current implementation works as a standalone tool in OpenWebUI, the real potential lies in developing dedicated Model Context Protocol servers for audio manipulation. Here’s how this could evolve:

Audio-Specific MCP Servers

Audio-focused MCP servers could provide LLMs with direct control over:

- Scale-Based Synthesis - Generate patterns based on modal characteristics

- Real-time Audio Analysis - Analyze recorded audio for its modal content

- DAW Integration - Send MIDI data or control parameters directly to digital audio workstations

- Sample Retrieval and Manipulation - Find and transform audio samples to match specific modal characteristics

The key is that MCP just provides an interface with the rest of your code. So you can leave the probabilistic nature of LLMs to your conversation, and rely on steady code for the heavy lifting.

Example Interaction

Imagine prompting an LLM with:

“Create an evolving pad sound based on Merlet’s Mode 3 with increasing tension over 16 bars, export as MIDI and send CC parameter automation to my instance of Serum2”

The MCP server would:

- Generate the Mode 3 scale structure (C E Ab)

- Create MIDI patterns emphasizing these notes

- Design synthesis parameters that accentuate the equidistant nature of the augmented scale

- Program automation curves that increase complexity over time

- Export directly to your DAW or synth

- see my previous post about scripting in REAPER

This level of integration would influence how we approach sound design, bridging the gap between theoretical concepts and practical implementation.

Conclusion

The marriage of specialized musical knowledge with the emerging capabilities of LLMs and Model Context Protocols could represent a new interface for audio folks. By building tools that encapsulate theoretical frameworks like Merlet’s modal system, we can make complex musical concepts immediately applicable to our creative workflows.

As we continue to develop these integrations, I hope that the boundary between conceptual thinking and implementation will become increasingly fluid. Sound designers should be able to move seamlessly between high-level musical ideas and their concrete realizations. I’ll be diving into this more going forward 🫡

-

Notice I didn’t say split evenly – while this system does work whether using just intonation/equal temperament/something else, it was described to me in the context of Western tradition, so the rest of this post will follow suit. But, at the end of the day its splitting octaves, so if you want to keep going past 12, go for it! You’ll end up with some pretty cool effects 🤝 ↩︎